Lice on cattle is a common issue for producers and it seems to get worse as the temperature gets colder. Winter is already hard on cattle performance, so louse control is important to maintaining health and growth through the colder months. The economic impact of lice has been difficult to assess, but United States livestock producers lose approximately $125 million per year due to cattle lice, as estimated by the USDA.1

Lice Types & Species

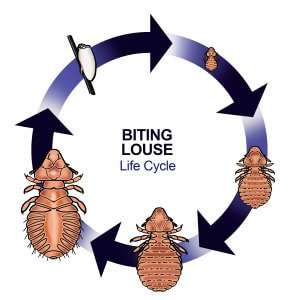

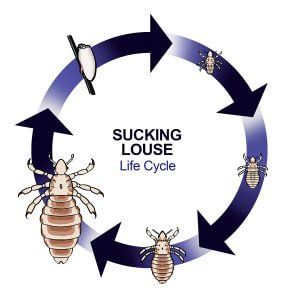

There are two main groups of lice that affect cattle: sucking and chewing lice. Sucking lice possess piercing mouthparts and take a blood meal from their host. Chewing lice, also known as biting lice, consume hair, skin, and sometimes blood from their host using chewing mouthparts.

Life Cycle Stages (starting with the white egg and moving clockwise):

Egg → First Nymph → Second Nymph → Third Nymph → Adult

Differentiating between the two groups of lice is as easy as looking at their head: sucking lice will have a head that is pointed and much more narrow than their thorax (the segment where insect legs attach), while chewing lice will have a broad head that is at least as wide as their thorax.

You may encounter any of five species within these two groupings of lice:

- The cattle biting louse (Bovicola bovis)

- The long-nosed cattle louse (Linognathus vituli)

- The little blue cattle louse (Solenopotes capillatus)

- The short-nosed cattle louse (Haematopinus eurysternus)

- The cattle tail louse (Haematopinus quadripertusus)

Chewing lice cause cattle to rub on fences to satisfy the itch caused by an infestation, while sucking lice can cause more detrimental effects such as anemia. Any infestation of lice will result in decreased growth and performance of cattle as a result of pruritus, hide damage due to scratching, and decreased weight gains.

Treatment & Control

Pediculicides are insecticides that target louse infestations. Systemic products like avermectins are often used to treat sucking lice, while spray-on and pour-on insecticides are suggested for chewing lice. Initial applications of pediculicides should take place in late fall before temperatures become too cold for whole-body treatments and the louse population increases.

Due to the life cycle of lice, plan to retreat the herd approximately two weeks after initial application in order to kill lice nymphs that may have hatched from presumably unaffected eggs. During extreme cold weather, pour-on and spot-on insecticides may be an acceptable option as to not stress cattle by wetting them in low temperatures. It should be noted that pour-on and spot-on treatments may not be sufficient for heavy lice infestations.

Due to the life cycle of lice, plan to retreat the herd approximately two weeks after initial application in order to kill lice nymphs that may have hatched from presumably unaffected eggs. During extreme cold weather, pour-on and spot-on insecticides may be an acceptable option as to not stress cattle by wetting them in low temperatures. It should be noted that pour-on and spot-on treatments may not be sufficient for heavy lice infestations.

Year-round control with topical insecticides can give advantage to the producer by keeping ectoparasites like lice and flies below an economic injury level. Additionally, livestock producers have reported that the use of pyrethrin-based insecticides during the spring and summer fly season seems to eliminate one or more lice treatments in the winter.

Oil-based insecticides are often preferred for lice infestations because the oil carrying the insecticide will help to penetrate the hair better than water and cling to the hide where the lice frequent. In addition, oil-based applications will prolong the residual effects of an insecticide application because it will not be easily washed off.

A supplemental form of control are dust bags containing insecticides. These can be placed in strategic areas such as near water, feed troughs, and at entrances to shelter and involve little labor to install and maintain.

As a final reminder, plan to treat cattle using the maximum dose on the label. This will reduce the risk of developing insecticide-resistant lice by killing most of the population instead of inoculating them with a low dose. Louse infestations should subside in the spring months as cattle begin to shed hair and spend more time in warm, direct sunlight.

Learn more about MGK’s pyrethrin-based products for louse and fly control:

Evergreen® Pro 60-6 | ULD® BP-100

Literature Cited:

1. Campbell, J. B. 1992. G92-1112 Lice Control on Cattle. Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. Lincoln, NE.